Why Are Some People Unable to Wink?

An incredibly complex process can go right or wrong in the blink of an eye

ou are sitting at a bar and see someone who catches your attention. You look in their general direction when suddenly they make eye contact.

You get flushed and embarrassed but then they give you the “signal” by winking at you.

Or, by blinking at you, as I found out the first time my future wife tried to wink at me. I did not know that some people could not wink until I met her. “That girl blinks emphatically,” I thought to myself the first time she attempted. But her lack of unilateral eyelid control made me wonder about the mechanism and what differentiates a blink from a wink.

It turns out that most people who can wink, can do so only with one eye or the other. The theory has been that it is genetic, rather than learned.

But a 2019 study published in the journal Brain and Behavior challenged that assertion by analyzing people who could all wink, but with varying abilities. Of those who could wink with only one eye, half learned how to wink with both eyes within one month.

So yes, winking can be learned.

And no, a blink is not the plural of a wink.

Blinking, fast and slow

Blinks are a rapid and transient closure of the eyelid. They typically occur unconsciously, roughly 15 times per minute. Blinking protects your eyes from external damage and lubricates them to prevent drying. But there are different types of blinks:

Reflexive blinks occur unconsciously in response to an outside stimulus.

Voluntary blinks occur consciously.

Spontaneous blinks, the most common type, occur unconsciously and are not typically evoked in response to stimuli.

The closure of the eye varies based on the type of blink. Reflex blinks are the fastest while voluntary blinks and spontaneous ones are slower and slowest, respectively. Since reflex eyelid closure occurs to prevent damage to the eye, evolution has made this the fastest. Spontaneous blinks are just to keep the eye moist, so they can take their sweet time.

Spontaneous blinking is controlled by the frontal lobe. But voluntary blinks are different.

Muscles and nerves around the eye

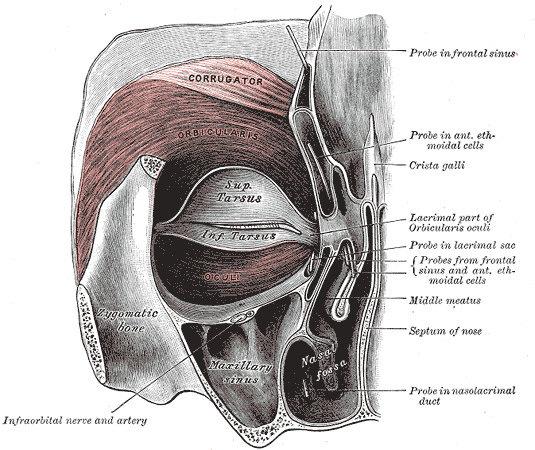

The way to describe a wink, in medical terms, is the contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle which surrounds the eye. The buccal branch of the facial nerve controls this muscle. A bit deeper is the levator palpebrae superioris, which elevates the eyelid when it is contracting. This is controlled by the oculomotor nerve.

Usually, damage to the individual nerve will affect the control of these muscles. This happens in a condition called Bell’s Palsy, whereby the facial nerve is inflamed. This stops the ability to close the eye on one side of the face because the orbicularis oris muscle cannot contract on the damaged side. We can think of these nerves and muscles as “local” control of the ability to close the eye but there is also “global” control as related to the parts of the brain that are activated during winking and blinking.

A wink really makes you think

Holding back a blink, from your brain’s perspective, is much harder to do than the act of blinking. Despite the complex nerve innervations of the various muscles involved in closing and opening the eye, overriding the automatic process of blinking takes a lot of brain power. Spontaneous blinking activates the frontal lobes. But holding back a blink was noted in many regions including parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes.

Likewise, different brain regions are activated depending on the side of the wink. For those who could not wink with the left eye, trying to do so caused activation in the bilateral frontal lobes, with the left frontal lobe having a bigger role. For those who could not wink with the right eye, successful winking was associated with activation only in the right frontal lobe.

But for people who suffer strokes and lose the inability to open their eyelids, one study showed that only the right hemisphere of the brain was affected. This suggests that eyelid control in the brain is under the influence of the right cerebral hemisphere.

In a study of 27 stroke patients with the ability to open their eyelids voluntarily, mapping the brain showed that the stroke had affected an area of the brain called the insular cortex, or insula. The insula is part of the cerebral cortex and has a role in a variety of functions ranging from sensory processing to representing feelings and emotions. 70% of patients in the study had lesions mapped to the right part of the brain.

The fact that eyelid opening is controlled by such a complex region of the brain makes sense. Taste, hunger and emotions are controlled by the same region of the brain. That may be why our brains interpret winks as such emotional gestures.

But when my wife blinked at me, I knew she loved me twice as much.

FollowAha!for more amazing science behind life’s most intriguing, strange and unexpected questions, likeWhy are Yawns Contagious?